THESE APPS ARE THE UBER OF BIRTH CONTROL

Via Refinery 29

The last time I had a UTI, I ended up in emergency. Not because it was a particularly terrible bladder infection (just your standard below-the-belt hell). But because, like 4.8 million Canadians, I didn’t have a regular family doctor. As I sat in the waiting room for hours on a Sunday evening alongside people who needed actual help, I thought, There has to be a better way.

Turns out there is. I could have texted a doctor from the comfort of my couch and probably gotten a prescription that evening if I used the app Maple. For a fee, Maple connects patients with one of over 400 doctors across Canada for a consultation via message or video in less time than it takes to get an Uber. Akira and Tia Health offer the same, no-wait services on their platforms. Or, if I preferred to see a physician IRL, I could have booked an appointment at Toronto walk-in clinic Care& Family Health via its app during regular business hours and be seen within five minutes (yes, that’s minutes, not hours) of my request.

DM-ing a doc may become the new normal as more Canadians access virtual health care. Hundreds of thousands of us have used apps and websites like these, and that number is likely to increase given that two-thirds of Canadians are up for trying time-saving health-care tech, according to a 2018 survey from the Canadian Medical Association.

“Over and over again, I would see people in the waiting room waiting four to six hours for very minor conditions,” says Dr. Brett Belchetz, a Toronto-based emergency room doctor and the co-founder and CEO of Maple. “When I would ask patients, the answer was always the same… they didn’t have a doctor or it was impossible to get an appointment in a timely way.” Maple, which launched in 2016, now has almost half a million Canadian users, who either pay per visit ($49–$99, depending on the time of day, plus prescription fees) or sign up for a monthly subscription ($30).

Certainly convenience is a major draw for users of virtual care. We order our food on apps, shop on our phones, date via DMs and texts — why shouldn’t we be able to use the same methods to consult a doctor for routine medical issues like UTIs, STIs, cough and cold, and non-narcotic prescriptions like birth control? I mean, pre-virtual medicine, god forbid you forgot to refill a prescription outside of business hours.

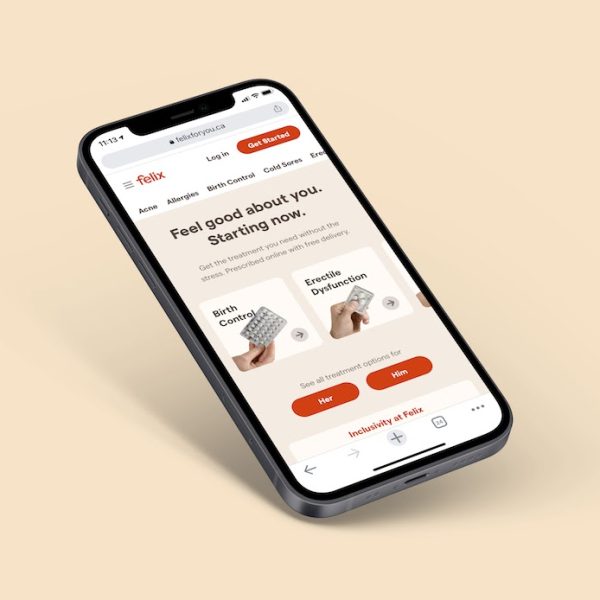

That’s why Toronto-based writer Kate Carter Hickey started using Felix, a digital health-care platform that specializes in four categories of prescriptions — birth control (minus the IUD), erectile dysfunction, acne, and hair loss — and delivers them across Canada, usually within a day. Carter Hickey had lived in South Korea, where birth control is available over the counter. When she returned to Canada, she had to see her doctor to refill her prescription and return for a follow-up three months later. “I think it’s unreasonable for anyone to have to take several hours out of their day to go see a doctor… especially for a routine prescription,” she says. Felix, which charges a $40 flat rate, streamlined the process. Carter Hickey filled out a questionnaire, which was reviewed by a doctor, then a year’s prescription was delivered to her door.

Serving the needs of Canadian women is a priority for Felix executives, especially when it comes to reproductive health, they tell me. Felix is hoping to make Plan B available on its platform by March, and is looking into the abortion pill, Mifegymiso. (Currently, you can request it on Maple, but it’s up to the doctor to decide whether they are comfortable prescribing it; if not they will most likely refer to another physician on the app.)

Virtual medicine offers something else traditional health care doesn’t: anonymity. Not everyone might feel comfortable going to the doctor they’ve had since they were five to ask for contraception or to look at this funny red thing that may be an STI, and then go to their local pharmacy to have the prescription filled.

But what if you can’t afford it?

Health care in Canada is supposed to be free and accessible to everyone. Virtual medicine, while covered by some private health insurers like Sun Life, isn’t part of any provincial health plan (outside of B.C.), so a part of the population, often the most vulnerable, is automatically excluded from accessing these resources. You also have to be 18 to use the majority of apps, which isn’t all that helpful if you live in a small town far from sexual health clinics and don’t want your mom or dad’s permission for a birth control prescription.

“We need to find a better way to give access to the same quality of service and the same confidentiality to every woman,” says Aude Motulsky, a professor at the University of Montreal School of Public Health. “I’m not sure if this is the answer.”

Still, proponents of virtual health care argue that by offloading clients who are willing to pay for services will decrease the toll on the system, including reducing wait times and doctor strain, and improving access for people who live in underserved rural areas.

Time will tell if that’s the case. But with more and more apps hitting the market and others expanding to include dermatology, lactation consultations, psychiatry, and more, accessing support online will be easier than ever.